Alumni Magazine Feature: The Influence of Race, Politics and History

June 9, 2022

Taurus Burns (‘02, Art Practice) has always wanted to create art that told stories through realism, and does that through his discussions of Black history in his work.

After an elementary school teacher called attention to and encouraged his budding talent, Taurus Burns knew that he wanted to be an artist when he grew up. An “Army brat” whose father was in the military, he had lived in four different states and two countries by the time he was 13-years-old. Along the way, he took to drawing as a form of self-expression and to record his experiences. “Growing up, I yearned to make art about my upbringing in a way that felt deeply personal, yet of the moment,” he recalls.

Taurus Burns, “The Graduate” Oil on Canvas

After graduating from CCS, Burns stayed in Detroit and became active in the local arts scene. Over the next decade, he could be found street painting at area art festivals, organizing shows with the exhibition committee at a popular gallery, and painting murals, and other public art projects—all while regularly exhibiting his art throughout Metro Detroit.

In 2012, he began a series that eventually grew to be 300 urban landscape paintings inspired by the city.

“Even though I had lived here for ten years, I still felt like an outsider,” Burns said. “I wanted to feel like a part of this city, to understand what it meant to be a Detroiter. I started going out to explore the landscape, and got to learn more about the city through the people I met at my art shows.”

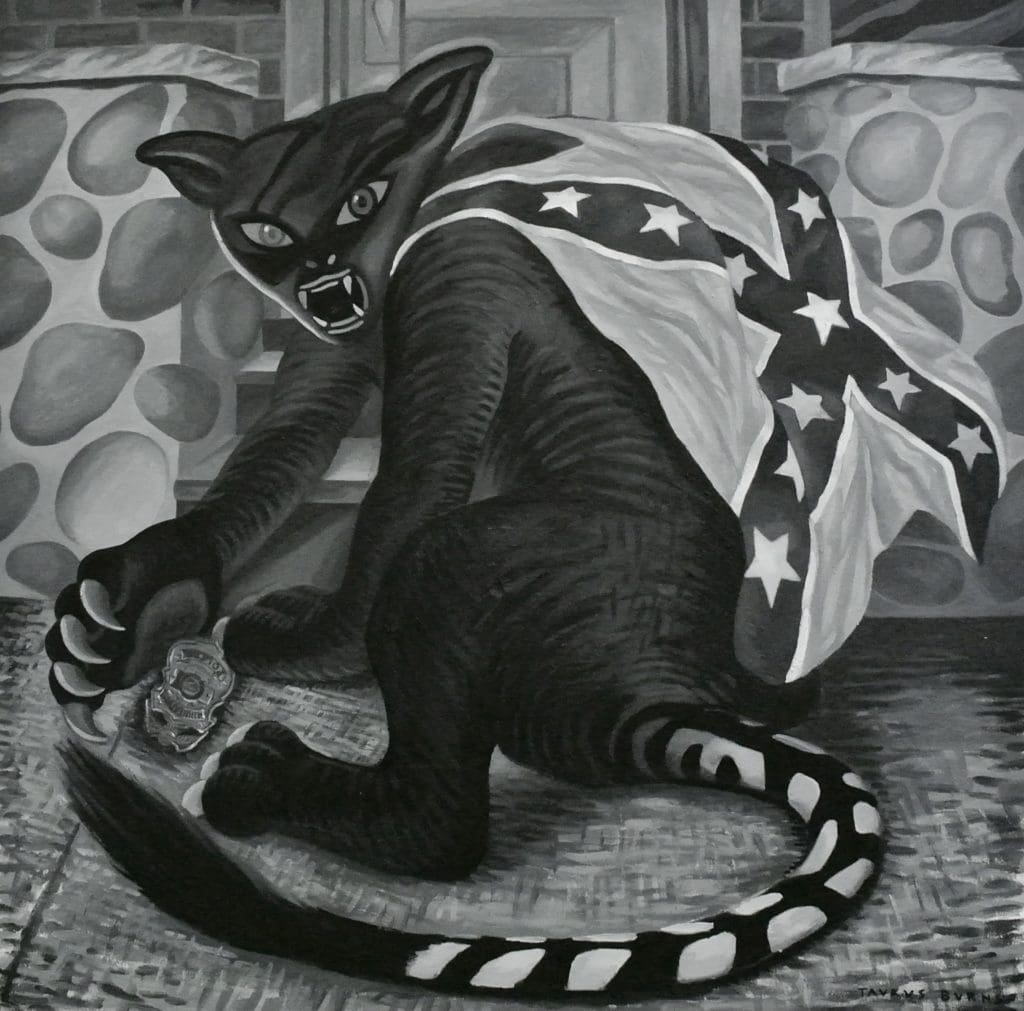

Taurus Burns, “Self Portrait as a Panther” Ink and Gouache on Paper

As he continued to build a life in Detroit, events around the country began weighing heavily on him. Stories and videos of Black people being killed by law enforcement had been surfacing for years. With the murder of Philando Castile, Burns says “Something in me broke.” Castile, a 32-year-old Black man, was shot and killed at a traffic stop in Minneapolis. His last moments were caught on camera by his girlfriend beside him in the car. This event caused a shift in Burns’ work towards confronting America’s ongoing problems with race.

This led to a groundbreaking solo show, “Troublemaker,” where he challenged the general perception of Black people as troublemakers in society, while celebrating Black artists, entertainers and leaders who had made an impact on identity and American culture. Of this exhibit, he says:

“I have dealt with that negative perception throughout my life. With this exhibit I was trying to do two things at once: address the ongoing deadly incidents of police violence towards Black men and also come to terms with my own experiences of racism. That show was the first time I pushed back against both.”

Since “Troublemaker,” Burns has continued to tackle said elephant in the room. His next exhibit, “Racism Sweet Racism,” was held at the Elijah Wheat Showroom in Brooklyn, New York. It featured portraits of Black and Trans women killed by law enforcement, as well as paintings that examined his ideas about a relationship between patriotism and institutional racism.

During the next couple of years, he continued to make art that touched on these subjects. And then, in 2020, George Floyd was murdered, sparking an outrage that swept across the nation and around the world.

Floyd was a Black man who a Minneapolis store clerk suspected of using a counterfeit $20 bill. Shortly thereafter, he was arrested by police and died after an officer kneeled on his neck for more than nine minutes.

Burns later attended a protest with his stepson, and couldn’t stop thinking about the effect that seeing the video of Los Angeles Police Department officers beating Rodney King had on him in 1991, at 17-years-old, and that his stepson was experiencing George Floyd’s murder at that same age now.

“It just solidified the importance of making work about this issue. America’s continued distortion of Black lives is disheartening, and it’s pushed me to continue fighting against this systemic problem,” Burns states.

Taurus Burns, “The Spirit of Fred Hampton” Oil on Canvas

Recent exhibits, “The Panther in Me” and “DEFENSIVE” continue the discussion of race in America. Burns surmises, “Because I’m biracial, I feel like I grew up between two races, but it’s like my life was set up for me to talk about race in this particular way. It’s not always easy, but it feels incredibly rewarding to finally be able to make this art.”